Crewlid Frank Staley

Gemeente Culemborg > Gesn. geallieerde militairen

Prisoner No.54

The Life of Warrant Officer Frank Staley; 633860

1920-1965

by

Wesley Eyley

Introduction

When looking at the Topic of the Second World War it is obvious, to me, that we cannot just look at the larger, publicised stories. The popularisation of the ‘peoples war’ and tales of great heroism such as Battle of Britain aces, or Soldiers who acted gallantly in the field of battle are all well and good, make you extremely proud to be British and make war stories more exciting. However we cannot ignore the untold stories that reveal different sides and indeed attitudes towards conflict and the troubles and hardships it can bring. In this era of popular history where programs such as ‘Who do you think you are’ and websites like ‘ancestry.com’ and ‘findmypast.com’ are making genealogy much more prevalent with history becoming more accessible; not just history books, but censuses and war diaries are bringing archives into the homes of those who want them. It therefore makes sense to reveal and tell one of these stories that would normally go untold and remain hidden, despite adding a contrary view to a generally accepted topic. Having said this, these popularised stories and recounts of events do offer us a background and setting for us to then evaluate and compare to the individual stories and lives that remain to be told through mediums such as this and the Memories of War Project.

We start with my Uncle Frank who thanks to my grandparents’ stories throughout my upbringing became instilled in my memory. My Granddad telling me the vague story of his time as a Prisoner of War which is something I have always been intrigued by and wanted to learn more about. Frank was my Granddad’s uncle, one to whom he was really close.

My Uncle Frank was born, Frank Sidney Staley, on the 11th May 1920, to Sidney Staley and Miriam Chamberlain of Swadlincote, South West Derbyshire. He was born into a working class family with his Dad, a Potter at the locally pottery[1]. Frank had an above average education being schooled at Ashby Grammar School, where he received consistent school grades and good reports from his teachers.[2]

I have divided this 40 year period of investigation into sub-categories; of his pre camp life, camp life and post camp life for which I have gathered large numbers of primary sources on which to base my findings as well as secondary sources to compare to the wider published stories.

RAF Career (1939-1940)

Handley Page Heyford circa 1930’s

After School Frank became a Laboratory assistant at Repton School, under Dr Barton. In January 1939, after reports of war on the horizon, he signed up for the RAF and was streamed to become a Wireless Operator/Air Gunner. Following initial training he was posted to No.3 Air Observer School, at RAF Aldergrove in Northern Ireland, where he trained on the Handley Page Heyford Aircraft; an outdated 1930’s Biplane Bomber. On 3rd November 1939, following 19 Hours of flight time training; he qualified as an Air Gunner and as a result was deemed combat ready[3]. He was then attached to 58 Squadron, which itself came under No.4 Group, RAF Bomber Command, based at RAF Boscombe Down in Wiltshire. Upon arrival at 58 Squadron Frank converted to the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley, a monoplane Bomber which replaced the outdated Heyford[4]. Just before Frank’s arrival, in October 1939, 58 Squadron became affiliated with Coastal Command, taking part in Anti-Submarine Patrols and Convoy Escorts. Frank took part in 3 sorties like this within a week; each time being airborne for periods of 6 hours or more[5] which shows the large workload that was expected of these young men. This also links with Chris Ward’s research in 4 Group, Bomber Command an Operational Record where he says ‘the winter of 1939/40 was harsh, and Whitley crews suffered unbelievable discomfort from the extreme cold inside their unheated aircraft’[6] he goes onto relate this to the character of the young crews ‘it speaks great volumes for the courage and determination of the crews’[7]

When 58 Squadron reverted back to the control of Bomber Command, in the month that followed, Frank took part in many raids on enemy territory including a propaganda drop[8] and an attack on the Fiat Factory at Turin in 1940, following the Italian’s entrance into the War. During this raid his aircraft and crew had to fly to Guernsey in order to refuel for the flight to Turin. He speaks of this detachment in a letter home to his mother, Miriam; ‘did you get my postcard…from the island of Guernsey we were only there for 4 or 5 hours, I would like to be posted there, it would suit me down to the ground.’[9]

The crew photograph infront of a Whitley. Frank is far left with what appears a cigarette stuck up his nose.

On the 17th June, 5 days after Frank was promoted to the rank of Sergeant[10], 58 Squadron were assigned with the bombing of an Oil plant at Gelsenkirchen which was a part of the German industrial heartland. The mission was to be a covert, night operation (a raid suited to the Whitley aircraft.) This was to be the start of a large 5 day offensive intended to weaken the Ruhr  manufacturing district. Frank’s Aircraft N1463 took off at 21:15 from RAF Linton-On-Ouse. (see picture next, taken at that moment!) Sadly 90minutes into the flight the Pilot, Flight Sergeant Ford, contacted group concerning a fire on board the Aircraft. Then over an hour after this initial contact, at 00:52 the following morning, they tried to attract the attention of another Aircraft[11]. It turns out the Aircraft suffered an engine failure and crashed on the south bank of the River Lek at Beusichem, which killed the pilot and Navigator whilst my Uncle Frank along with 2 colleagues, the second Pilot and gunner became the first members of 58 Squadron to fall into enemy hands[12]. The picture above shows My Uncle Frank on the far left with his crew other members of 58 Squadron preceding this crash on the 17th June 1940. The IWM also holds a photo of Frank’s aircraft, N1463, taking off just days before it crashed.[13]My Uncle Frank became the 54th Prisoner of War to be captured by the Germans, one of over 135,000.

manufacturing district. Frank’s Aircraft N1463 took off at 21:15 from RAF Linton-On-Ouse. (see picture next, taken at that moment!) Sadly 90minutes into the flight the Pilot, Flight Sergeant Ford, contacted group concerning a fire on board the Aircraft. Then over an hour after this initial contact, at 00:52 the following morning, they tried to attract the attention of another Aircraft[11]. It turns out the Aircraft suffered an engine failure and crashed on the south bank of the River Lek at Beusichem, which killed the pilot and Navigator whilst my Uncle Frank along with 2 colleagues, the second Pilot and gunner became the first members of 58 Squadron to fall into enemy hands[12]. The picture above shows My Uncle Frank on the far left with his crew other members of 58 Squadron preceding this crash on the 17th June 1940. The IWM also holds a photo of Frank’s aircraft, N1463, taking off just days before it crashed.[13]My Uncle Frank became the 54th Prisoner of War to be captured by the Germans, one of over 135,000.Camp Life (1940-1945)

It seems that I should start this section off with a disclaimer that not all of camp life can be stereotyped with the images portrayed in ‘The Great Escape’ and ‘Escape to Victory.’

This project opens up a different story of life in a Prisoner of War Camp in Germany. It is clear that despite the large amounts of evidence concerning what my Uncle Frank was able to achieve in his time in captivity he was still imprisoned for 5 years, in less than desirable conditions, it still is hard to believe the conditions that he had to put up with for so long. Having said this, his friends certainly gave the job of describing their collective experience a damn good try.

Frank was reported missing on the 18th of June 1940 and his parents received a telegram with this in brief on the 19th June.[14] This was immediately followed with a Letter which provided more information and passed on the sympathies of the RAF at this News. Following this, on the 1st July 1940 they received another letter informing them that Frank had indeed been captured and was a Prisoner of War in the Dulag Luft (A transit camp for RAF personnel before they were moved to an official stalag.) Here all prisoners of War were interrogated so the enemy could find out as much information as possible. Donald Morris recalls his experience at the same camp; ‘each airman was collected for interrogation in the middle of the night. The interrogation took place in the commandant’s office, and various tactics were used to get us to talk including the firing of pistols in nearby rooms to make each airman think that their colleague had been killed.’[15] It is impossible without German records to ascertain the order of the camps Frank was a prisoner at, he was moved between 3 camps; Stalag Luft III, VIII-B and 357. However thanks to his YMCA Logbook his last camp was Stalag Luft 357 at Fallingbostel.

Group camp photo. Frank is towards the right with a hat on

Despite not being able to pinpoint my Uncle Frank at camps between exact dates, thanks to his personal documentation and photographs it is easy to piece together what kind of life he led inside the camp. In a letter to his Mother, Miriam, dated June 1941 he states ‘I spend most of the day either reading, playing cricket or sunbathing. I am quite brown now.’[16] Alongside these letters it is clear to see that he also spent some time taking part in amateur performances with fellow camp mates. A past time enjoyed by most Prisoners of War.[17]

Frank also differs from some Prisoners of War in that he wanted to prepare himself for leaving and returning to ‘civvy street’ whilst in the camp he was able to complete Level 1 and 2 of Technical Electricity, in 1943, from the City and Guilds Institute. After passing it was reported at home in the Burton Observer as an example of camp life.[18]He was also promoted to a Warrant Officer in the camp, the highest NCO rank achievable in the Royal Air Force.

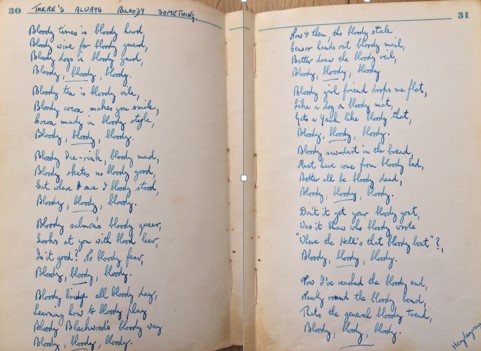

As well as these pictures and letters Frank’s friends were also pro-active in making sure their time was well remembered and well documented. Frank’s YMCA Logbook[19] contains not just stories or signatures but humorous poems written about life in the camp. Poems for ‘Stal’, as he was known, such as ‘There’s Always Bloody Something[20]’ a rather amusing poem about life their ‘bloody’ rotten time, and ‘Smoke’ which refers to London and its popular northern nickname, as well as detailed drawings of the billet in which he lived, which also manages to jovially mock Frank’s City and Guilds course, and even a personalised crest which is attributed to my Uncle Frank’s keenness and ability for Bridge. These poems, drawings and stories represent the comradeship these men all shared in the common cause of getting home. My Uncle Frank’s closest friend in the camp was Arthur Hadley, also known as ‘Curly’ - shown above - someone to whom he remained close right up until his death. It also shows the want of keeping this friendship had an air of continuation as they are signed and dated in order to hopefully remain in contact after the war is over.

As well as these pictures and letters Frank’s friends were also pro-active in making sure their time was well remembered and well documented. Frank’s YMCA Logbook[19] contains not just stories or signatures but humorous poems written about life in the camp. Poems for ‘Stal’, as he was known, such as ‘There’s Always Bloody Something[20]’ a rather amusing poem about life their ‘bloody’ rotten time, and ‘Smoke’ which refers to London and its popular northern nickname, as well as detailed drawings of the billet in which he lived, which also manages to jovially mock Frank’s City and Guilds course, and even a personalised crest which is attributed to my Uncle Frank’s keenness and ability for Bridge. These poems, drawings and stories represent the comradeship these men all shared in the common cause of getting home. My Uncle Frank’s closest friend in the camp was Arthur Hadley, also known as ‘Curly’ - shown above - someone to whom he remained close right up until his death. It also shows the want of keeping this friendship had an air of continuation as they are signed and dated in order to hopefully remain in contact after the war is over.Post War (1945-1965)

Frank arrived home in England after almost 5 years of imprisonment. He was able to send a telegram to his family on the 10th May 1945, saying ‘arrived safely feeling fine. See you soon.’ This was only 2 days after VE Day, showing that he and other prisoners were a high priority when it came to bringing them home.

After Frank had returned home in 1945 he was, thanks to his time in camp, ready for life after the war in ‘Civvy Street.’ Following his homecoming he returned to Swadlincote to 51 Belmont St. where after 2 years he met and married my Aunt Margaret. Following their marriage Frank and Margaret took Holiday to the Norfolk Broads[21] to get away from Swadlincote. 3 Years later in 1951 their first child was born, Jill Staley. They went on to have 2 more daughters; Elaine and Angela.

During the 1950’s Frank and his father Sidney set up a television shop in Swadlincote together; making use of Frank’s city and Guilds qualifications earned in 1943.

Sadly in January 1965, while Frank was running for a bus home, after locking the shop up, he collapsed after suffering a heart attack. The bus drove immediately to the hospital but sadly was too late. Frank passed away and left the shop, his wife Margaret, and 3 young daughters.

Sadly in January 1965, while Frank was running for a bus home, after locking the shop up, he collapsed after suffering a heart attack. The bus drove immediately to the hospital but sadly was too late. Frank passed away and left the shop, his wife Margaret, and 3 young daughters. When readdressing this matter now it could be argued that Frank’s time in prison may have had some effect on his post war life. Jill recollects that Frank never actively spoke about his RAF service or life during the war, only remembering seeing his logbook as a child. She realised the significance of his service life and experience following his funeral in 1965 when Frank’s best friend ‘Curly’ was present. This shows the friendship these men had; living in different parts of the country ‘Curly’ still came to Frank’s funeral. Their time in the camp had brought them very close.

Another instance Frank’s time as a prisoner of war might have affected his attitude to the war in general in the remainder of his life. In common with many others, he resisted talking about his war experience with his children. Jill, his eldest daughter, remembers this resistance and also recalls the intensity of his reaction when her father, as a former POW in Stalag Luft III, was invited to a local special showing of ‘The Great Escape’ in 1963. He refused to attend the event and Jill vaguely remembers his reason being his dislike for the way in which war being was glorified. Jill acknowledges that this could be her subsequent interpretation of the strength of his feeling, partly because for all of her teenage and adolescent life she has had an antipathy to all things military. It has only been in recent years that she has been more open minded and curious about war experiences. She, nevertheless, still avoids watching films about war and military conflict from all periods. She wonders if this is because she had no opportunity to talk through with her father his own experience and was not able to bring any perspective to what had been a formative period of his life as a young man.

Another instance Frank’s time as a prisoner of war might have affected his attitude to the war in general in the remainder of his life. In common with many others, he resisted talking about his war experience with his children. Jill, his eldest daughter, remembers this resistance and also recalls the intensity of his reaction when her father, as a former POW in Stalag Luft III, was invited to a local special showing of ‘The Great Escape’ in 1963. He refused to attend the event and Jill vaguely remembers his reason being his dislike for the way in which war being was glorified. Jill acknowledges that this could be her subsequent interpretation of the strength of his feeling, partly because for all of her teenage and adolescent life she has had an antipathy to all things military. It has only been in recent years that she has been more open minded and curious about war experiences. She, nevertheless, still avoids watching films about war and military conflict from all periods. She wonders if this is because she had no opportunity to talk through with her father his own experience and was not able to bring any perspective to what had been a formative period of his life as a young man.Frank was intellectually curious and interested in applying his practical knowledge. He stimulated interests in his children. The first Christmas present that Jill can remember was a Mecano set. She remembers her father buying equipment and chemicals so that she could have her own chemistry set, and recalls trips to London, reading a wide range of newspapers and her father wiring speakers into their bedrooms so that he could talk to them and wake them in the mornings. Frank took, developed, tinted and printed his own photographs, including many of his young wife, Margaret. While Frank had a wide range of interests and a job that brought him into contact with many people, he did not have a wide social circle. He did not, for example, spend time in pubs or at working men’s clubs as so many of his generation did. It could be that his long period of time as a young prisoner of war influenced his interests and activities.

Having said this however everyone was very fond of Uncle Frank and he was a very caring man. So much so that when customers could not make payments for a hire/purchased television my Uncle Frank would make the payment for them; something that almost bankrupted his family after his death. This was also apparent in his relationship with his wife Margaret; he would never go to sleep on an argument and would always tell her that he loved her before going to bed.

Conclusion

Above all this research on the life and experiences faced by my Uncle Frank, and many others like him, has given me a completely different outlook on Prisoners of War; in terms of their treatment but also what it did to them as indivuals and the profound effects it had on their lives. Despite Frank having to face the horror of bailing out of a crashing aircraft and nearly 5 years as a prisoner of war, he was safe. He was alive. He did not have to risk his life further by conducting more missions over enemy occupied territory, which he would have had to do. 55,573 members of Bomber Command lost their lives in World War 2 and Frank could have done.

Above all this research on the life and experiences faced by my Uncle Frank, and many others like him, has given me a completely different outlook on Prisoners of War; in terms of their treatment but also what it did to them as indivuals and the profound effects it had on their lives. Despite Frank having to face the horror of bailing out of a crashing aircraft and nearly 5 years as a prisoner of war, he was safe. He was alive. He did not have to risk his life further by conducting more missions over enemy occupied territory, which he would have had to do. 55,573 members of Bomber Command lost their lives in World War 2 and Frank could have done. As stated above when addressing the effects upon Frank; he had seen first-hand the horrors of war and he had lived as a prisoner, because of this Frank could not condone the glorification of war that films and popular theories of the ‘people’s war’ have done. With this research it is clear to see why.

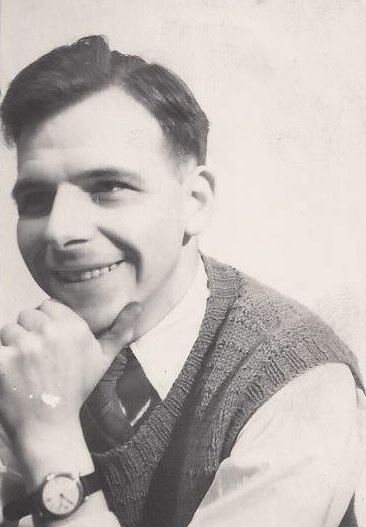

Overall Frank did not let his wartime experience show, on the outside, but as stated, we can never know the full story regarding his capture and imprisonment. This picture, I feel, depicts Frank as he was remembered by family; as a much appreciated, kind, caring, genuine and thoughtful gentleman, even in the face of his war time experience.

Overall Frank did not let his wartime experience show, on the outside, but as stated, we can never know the full story regarding his capture and imprisonment. This picture, I feel, depicts Frank as he was remembered by family; as a much appreciated, kind, caring, genuine and thoughtful gentleman, even in the face of his war time experience.